10-8-2002

CUBA e FIDEL

17 May 2002 11:06 GMT+1

The last days of Castro

|

The visit to Havana this week of a former US President has brought one thing into sharp focus: Fidel Castro, the world's most famous revolutionary, is entering his twilight days after four decades in power. Some are even asking: what next for Cuba, the last bastion of Communism in the West? |

|

|

|

By Simon Calder

17 May 2002

Her Majesty the Queen and Fidel Castro are, as far as I can ascertain, strangers. A shame – they share much in common. They are among the world's longest-reigning heads of states, and each has an impending golden jubilee. Next month, the Queen celebrates 50 years since she ascended, peacefully, to the throne; next year, it will be half a century since Dr Castro led a team of rebels into abject, bloody failure. And this week, as the former US President Jimmy Carter made a historic visit to the island, many watching the footage of the two elderly politicians started to think the unthinkable – that Castro cannot continue forever, and when these, his twilight years, finally come to an end, the island will change irrevocably. Will whoever takes over from Castro – and who that will be is itself unclear – make the democratic reforms that Cubans are starting to demand?

The assault on the Moncada Barracks in Santiago de Cuba on 26 July 1953 would have been comic – some revolutionaries turned up at the target by taxi – were it not so tragic. Many rebels died at the scene; some survivors were tortured and killed in captivity; but Castro was spared to make his celebrated assertion that "History will absolve me". He was imprisoned and later exiled, where he met a young Argentine, Ernesto "Che" Guevara. The rest is history – a narrative that has been written by the victor since the triumph of the Revolution on New Year's Day, 1959. Unsurprisingly, the official chronicle makes heroes of the inept attack, deifies Che and provides Castro with absolution as advertised.

A more convoluted ascent to power, then, than simply waiting for nature and the British rules of succession to take their course and elevate one to the monarchy. Yet Elizabeth II and Fidel I would find plenty to chat about. Ruling a large, diverse island for much of your adulthood is tough. Take just one of the litany of titles that each must bear: he, First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Cuban Communist Party; she, Defender of the Faith. Their job descriptions are identical: protect the state ideology by keeping one step ahead of its mutations over time, making it appear that you are leading, rather than reacting to, shifts in opinion.

Dr Castro has been a far more effective non-elected head of state than the Queen. But then, he has had the advantage of being despised by the world's leading superpower for the past four decades – a condition that confers enormous mastery on a potentate.

Five out of 10: that is Jimmy Carter's position in the roll call of US presidents who have squared up to Castro. The first was Dwight D Eisenhower, whose last significant political act was to sever diplomatic links with Cuba on 3 January 1961. The last is George W Bush, who has assigned the island to the axis of evil, that select list of nations that the US despises to the depths of its nuclear arsenals.

Of the presidents who have squared up to Castro – the others being Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, Ford, Reagan, Bush Snr and Clinton – only Carter has shown any wit or wisdom in his dealings with Castro. The others have given the Cuban leader an ideological walkover for four decades.

Before 9 November 2000, I used to ridicule the way that candidates for the US presidency slavishly followed the hawkish agenda of the Cuban exiles in Miami. But on that morning I took a flight from Gatwick to Havana. Before take-off, the pilot announced George W Bush was the new President; by the time we touched down, he had been temporarily unanointed. Bush's vituperative anti-Castro rhetoric was to prevail in the ultimate swing state. Al Gore was perhaps wounded by the Democrats' insistence on doing the right thing in returning the schoolboy, Elian Gonzalez, to Cuba. So Castro indirectly handed power to Bush, returning the favour that has shored up his regime since the Revolution.

What more could a dictator need? Its neighbour had spent the first 60 years of the 20th century running Cuba as a semi-detached state – and a source of cheap sugar, sex and salsa. No more Mr Nice President: when Castro started to implement reforms, and laid the foundations for vast improvements in health and education, the White House turned nasty. Its incumbents filled the remainder of the century with a spite that played into the hands of the man the Americans sought to destroy. With every CIA assassination attempt – most as pathetic as the attack on Moncada – Castro's legitimacy grew. The attempts to destabilise the revolutionaries helped the leader to justify political repression, while the economic embargo enabled the leader to evade blame for the gross economic mismanagement over which he presided.

At the same time, US bellicosity has helped the last bastion of Communism in the West become an immensely strong brand. Rare is the city without a Café Cuba, or the glossy fashion magazine without a photo-shoot in Havana. An island with fewer people than the state of Ohio and a dodgy government is lauded around the world. The economic embargo has backfired even more explosively than a 1957 Chevrolet that deafens passers-by as it splutters around the capital, carrying twice as many people as the Detroit original envisaged.

Cuba's wheels have not come off – despite the best efforts of Washington, and the collapse of the benefactors in Moscow who shored up the island for 30 years after Castro decided he was a Marxist-Leninist. In his address to the people of Cuba this week, Jimmy Carter made one mistake. He said, "Our two nations have been trapped in a destructive state of belligerence for 42 years."

The harm, in fact self-inflicted, caused by Washington's sanctions takes a bizarre range of forms, from denying US cigar and rum connoisseurs the premiers crus of their chosen indulgences to intensifying the global notion that the US is not the world's policeman, but rather its big, bad bully. Significantly, it removes free choice about where Americans may vacation. And the winner is... the British holidaymaker.

When the Cuban economy went into freefall in 1993, Castro correctly predicted that only tourism could save the island. With Spanish, Canadian and British partners, he turned Communism's last-chance saloon into a new Caribbean beach destination – which this week will welcome more British visitors than it did in the whole of 1989. In a normal world, the Americans would have outbid us for the best places in the sun on their nearest island. But the risk of being jailed in the US and fined $55,000 (£38,000) is enough to deter most American citizens from breaching rules designed to outlaw tourism to the Caribbean's largest and most beautiful island. While we benefit from cheap holidays, the US Treasury operates a Cuba Sanctions Violation Hotline, so that Castro-fearing citizens can grass on American travellers who enter Cuba via Mexico or Canada. Even Jimmy Carter had to ask nicely for permission to visit Havana.

Since 42 years of sanctions have had precisely the opposite effect to that intended, I suggest an alternative prospectus: victory through tourism. Allow 270 million Americans access to the island most of them have only dreamed about, and they will help expose the brutality of Castro's regime. When a million camcorders are rolling on Disneyland Havana, suppressing dissidence gets much tougher. Enough of the money that the tourists bring in will reach the people to liberate them from Castro's economic oppression. Watchers of the decline of Communism know the event that sealed the fate of the USSR was the day in 1989 when McDonald's opened in Moscow, revealing to the citizens what many took to be a virtue of capitalism. The Big Mac could succeed where the CIA failed in toppling Castro.

El Jefe has already worked this one out. That is why Castro is seeking to secure normality on his terms, and working with Jimmy Carter. But no one is sure whether he has calculated the answer to the question that concerns most Cubans more than "when will I be able to order a burger and fries to go?"; "who follows Castro?"

If our respective heads of state meet, the Queen could perhaps explain the benefits of a clear line of succession. In Cuba, there is no obvious successor. Castro's seed is scattered far and wide, with a couple of illegitimate daughters popping up in Miami. His brother, Raul, is widely cited as the successor, but as a fellow revolutionary he is part of the (very) old guard. As with the house of Windsor, there is talk of skipping a generation. But Castro is in no rush.

Shortly after the Eastern Bloc collapsed, Andy Kershaw made a thoughtful and perceptive series of programmes for Radio 4. The title was Castro's Last Christmas?. Few imagined that, a decade later, he would still be the heavyweight champion of the Third World, on a par with Nelson Mandela. South Africa's liberator knew when to stand down and blossom into elder statesman for the oppressed. Castro, who tasted only a morsel of prison life compared with Mandela's jail term, shows no such inclination to abdicate – rather like the Queen. Perhaps they are unsure of their successors' abilities to defend their divergent faiths. Meanwhile, I urge you and Her Majesty to visit Cuba soon, while the humanity that has sustained the people through centuries of hardship prevails – and before tourism claims another victory.

The unlikely island: things you never knew about Cuba

* Cuba's national airline, Cubana Airlines, has a poor accident record and scores F on a rating of air safety from A to F.

* Old Havana, where the crumbling grandeur of the buildings is the subject of many coffee-table books and fashion shoots, is a Unesco World Heritage site.

* The American naval base in Guantanamo Bay, home to Camp X-Ray, was built by the US in 1903 and has now been leased until the year 2033.

* Cuba's health system has been acclaimed by many – medical, hospital and dental care is free for all Cubans. Life expectancy on the island is 73 years for men and 78 for women.

* Santeria, a religious cult with similarities to voodoo, is claimed by its members to have as many believers as the Roman Catholic church in Cuba.

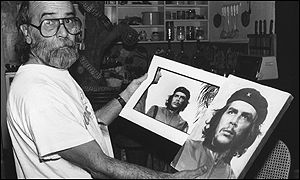

* The face of Che Guevara, possibly the world's most photogenic revolutionary, gave us the iconic image on a T-shirt that spread round the world. Alberto Korda, who took the photograph on which the image is based, is said not to have received anything in royalties for it. Guevara, first name Ernesto, was not actually Cuban.

* Baseball, that most American of sports, is also considered the national sport of Cuba. It was first played on the island in the 1860s.

* Cuban cigars, banned in the US along with other Cuban products, are widely available across America. There are 32 brands, none of which are handrolled on the thighs of virgins, but the best are made by hand and banded with a government seal.

* With no car imports, Cubans resort to ingenious repairs and modifications to old models dating back to the 1940s, such as fitting Lada engines in Chevrolets.

Simon Calder is travel editor of 'The Independent', and co-author of 'Cuba in Focus' and 'Travellers' Survival Kit: Cuba'

LINKS:

23-4-2003

Kuba

Entzaubert Trauer um Kuba: Die Linke kehrt Fidel Castro den Rücken

Von Paul Ingendaay, Madrid

Fidel Castro macht Fehler und merkt es nicht mehr: Das ist eine Wahrheit, an der selbst der wohlwollendste Beobachter nach den hastig vollstreckten Todesurteilen gegen drei Schiffsentführer sowie den massiven Gefängnisstrafen für fünfundsiebzig kubanische Dissidenten und Bürgerrechtler nicht mehr vorbeikann. Ein augenrollender Starrkopf rudert mit den Armen, um beiseitezufegen, was sich in seiner Umgebung regt.

Das Schauspiel ist so empörend wie rätselhaft. Denn vermutlich hat kein Diktator der Welt so viele Chancen bekommen, seine Herrschaft zu mildern und zu humanisieren; niemand hatte soviel Zeit wie Castro, Fehler auszubügeln und das marode System zu reparieren. Die letzten vier Jahrzehnte haben ja nicht nur gezeigt, daß selbst die kleinste Geste guten Willens wahrgenommen und akklamiert wird. Diese langen Jahre sind auch die Leistung einer tapferen, bewundernswert selbstgenügsamen Bevölkerung. Es könnte sein, daß die vereinzelten Solidaritätsadressen Prominenter in Richtung Karibik, ob sie nun von Diego Maradona stammen oder Gabriel García Márquez, in Wahrheit nicht dem greisen Führer, sondern vor allem dem kubanischen Volk gelten.

"Mit Überraschung und Schmerz"

Das Volk aber wird im allgemeinen nicht gefragt. Statt seiner reden die Künstler. Fast dreißig von ihnen, darunter international bekannte Namen wie der Schriftsteller Miguel Barnet, die Sängerin Omara Portuondo, der Liedermacher Silvio Rodríguez und der Filmregisseur Humberto Solas, haben soeben einen offenen Brief an ihre Kollegen aus Europa und Lateinamerika gerichtet, in welchem sie abermals um Solidarität bitten. Das Schreiben trägt den Titel "Botschaft aus Havanna an die Freunde, die fern sind", und wenn das Ganze nicht so trist wäre, könnte man sentimental werden. "Mit Überraschung und Schmerz", so heißt es dort, habe man in Kuba zur Kenntnis genommen, daß die Manifeste der "antikubanischen Propaganda" nicht nur die Unterschriften der üblichen Hetzer trügen, sondern auch "die geliebten Namen einiger Freunde".

Dann folgt eine logische Volte, die man in Osteuropa wohl besser zu würdigen weiß als anderswo: "Bedauerlicherweise und ohne Absicht dieser Freunde handelt es sich um Texte, die in einer großen Kampagne benutzt werden, um uns zu isolieren und das Feld zu bereiten für eine militärische Aggression der Vereinigten Staaten gegen Kuba." Das eigene Argument durchzuboxen, indem man die Gegenseite für ahnungslos erklärt, entspricht guter totalitärer Tradition. Diesmal jedoch werden die kubanischen Künstler - darunter approbierte Kollaborateure des Überwachungsstaats - wenig Erfolg haben. Denn am anderen Ende befinden sich meinungsstarke, kampferprobte Köpfe, um nicht zu sagen, ein gesammeltes Heer von Intellektuellen, das sich zu allen Themen zwischen Rüstungsindustrie und Ozonloch zu Wort zu melden pflegt, von Mario Vargas Llosa bis zu Günter Grass. Daß ausgerechnet Grass Gefahr laufen könnte, "das Spiel der Vereinigten Staaten zu spielen", wie der offene Brief formuliert, dürfte kaum jemand im Ernst befürchten.

Ebendarin liegt das Neue an der kubanischen Misere: Selbst linke Intellektuelle wenden sich in diesen Tagen entgeistert von Castros Staat ab, nicht nur ein Günter Grass, sondern auch bekennende Marxisten wie José Saramago oder Eduardo Galeano. Castros Trick, den Irak-Krieg als Paravent für die brutalste Repression seit Jahren zu benutzen, hat niemanden getäuscht. Kuba, eine viel zu lang gehätschelte Utopie, deren kräftigste Nahrung die oft tumbe Aggressivität des amerikanischen Nachbarn war, gibt sich als vergreiste Diktatur ohne einen Hauch gesellschaftspolitischer Vision zu erkennen.

"Vergesellschaftung des Elends"

Wie stark das im intellektuellen Milieu schmerzt, zeigt ein Beitrag des mexikanischen Schriftstellers Carlos Fuentes in der Dienstagsausgabe von "El País". Nach fast einem halben Jahrhundert kubanischer Revolution sei die Insel immer noch abhängig: seinerzeit von sowjetischen Subventionen, heute vom Tourismus und der Prostitution. In der Tat wird trotz flammender Revolutionsrhetorik des "Comandante" und Polizeipräsenz an jeder Straßenecke nirgendwo so unverstellt gehandelt und gehökert wie in Havanna: mit Zigarren, Wohnungen, Frauen.

Die "Vergesellschaftung des Elends", wie der im Londoner Exil lebende Schriftsteller Guillermo Cabrera Infante die kubanische Wirtschaftsform schon vor fast zwanzig Jahren nannte, läßt der Bevölkerung keine andere Wahl. Das bedeutet allerdings nicht, daß man sehnsüchtig auf den Kapitalismus des großen Nachbarn warten würde. Im Gegenteil, gerade die Kritiker Kubas erklären sich gleichzeitig zu Gegnern Amerikas. "Gegen Bush und gegen Castro", mit dieser Formel schließt der Kommentar von Carlos Fuentes.

Die Unwahrscheinlichkeit eines "dritten Wegs", der auch bei Fuentes als ferne Hoffnung aufschimmert, macht die Lage der Karibikinsel so prekär. Denn es gibt ja nicht nur die Konformen drinnen und die Systemgegner draußen, etwa im kubanischen Exil von Miami, das ein starkes Wählerpotential darstellt und bereit ist, zur Durchsetzung seiner Ansprüche erheblichen Druck auf die amerikanische Politik auszuüben. Es gibt auch die Bewohner einer buntscheckigen kubanischen Diaspora zwischen Paris, Madrid, Barcelona und Mexiko-Stadt. Und es gibt die stille Opposition auf der Insel selbst, Leute, die womöglich reisen dürfen, aber keine eigene E-Mail-Adresse haben, weil die Wächter des Systems "Subversion" und "antikubanische" Aktivitäten argwöhnen. Mit seiner jüngsten Repressionswelle hat Castro deshalb nicht seine erklärten Feinde getroffen, sondern die Moderaten, Bescheidenen und Geduldigen. So etwas nennt man Blindheit.

Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 23.04.2003, Nr. 94 / Seite 37

Literatur und

Politik

Verlorene Illusionen

14. April 2003

Der portugiesische Literatur-Nobelpreisträger José

Saramago hat die Hinrichtung von drei Entführern einer Passagierfähre und die

jüngsten Haftstrafen für Dissidenten auf Kuba scharf verurteilt und distanziert

sich von Fidel Castro.

„Kuba hat mit der Erschießung dieser drei Männer keine heroische Schlacht gewonnen, wohl aber mein Vertrauen verloren, meine Hoffnungen zerstört und meine Illusionen betrogen“, schrieb der kommunistische Autor in einem Beitrag für die Montagausgabe der spanischen Tageszeitung „El País“.

„Bis hierher und nicht weiter. Von nun an wird Kuba seinen Weg gehen und ich den meinen“, ergänzte Saramago, der die kubanische Revolution stets verteidigt, sich aber zunehmend von Staatschef Fidel Castro distanziert hatte. Nach den Worten des achtzigjährigen Schriftstellers müsse jeder das Recht haben, zu widersprechen. „Das kann zum Verrat führen, aber dafür muss es unwiderlegbare Beweise geben.“ Dies sei bei den jüngsten Schnellverfahren auf Kuba aber nicht der Fall gewesen.

Die drei Entführer waren wegen „Terrorismus“ verurteilt

und am vergangenen Freitag, eine Woche nach ihrer Festnahme, erschossen worden.

Es waren die ersten Hinrichtungen in Kuba seit drei Jahren. Davor waren zudem 75

Regimekritiker zu hohen Haftstrafen verurteilt worden. Die kubanische Regierung

wirft den Dissidenten vor, bezahlte Agenten der Vereinigten Staaten zu sein.

Cuba libre

On Fidel's island

fortress, dollar-fuelled hedonism and communist austerity live side by side. As

Castro enters the twilight of his rule, Ed Vulliamy experiences Stalinism

beneath the palm trees, and meets a new opposition leader whose quiet revolution

aims to topple the cigar-smoking dictator - by calling his bluff

Sunday May 12, 2002

The Observer

|

Lazaro Vargas, for all his strength, has a smile like melting honey. And with each crack behind him of horsehide against ash, each connection between baseball and bat, the muscles in his neck tighten as though it were some moment of impact within his own body. Baseball practice on the outskirts of Havana, under an impenitent Sunday sun, is just as earnest as in the United States. Only here the game is played for love and glory - by law - not for money. And for something else, or so they say: for Cuba. Vargas is one of the greatest players in the world, and the one thing that all fans of the game know about him is that he's the man who, as limousines prowled the streets of Atlanta during the Olympic games picking up Cuba's stars, turned down $6m to join the Braves baseball team. There is therefore one question all those fans want to ask Vargas: Why? He smiles that strong, sweet grin. 'It is a good feeling,' comes the reply slowly, 'to walk down the street knowing that no one can buy you.' Baseball is a uniquely ascetic game. To master it, you need the kind of inner peace Vargas exudes. It is, he says, 'a bit like Zen Buddhism; a game of amor y concentracion' - love and concentration. And: 'Yes, there is a connection between that and playing it for no salary. I have been playing baseball since I was my son's age,' he points to three-year-old Miguel Antonio, in an oversized helmet carrying an even more outsized bat. 'Why would I want to leave people who love me?' Lazaro Vargas is the model of Cuba's official self-image. He is a modern incarnation of the revolutionary hero, wearing sports kit rather than military fatigues. But he is not Cuba. It seems cruel that even such noble rhetoric should have a hollow ring in its echo. |

|

For out in that city - beyond fourth base and the white line in the dust - Havana is on the edge of Fin-de-Something... but Fin-de-What, exactly? The answer is as mercurial as the city itself and as ambivalent as Cuba's many faiths and faces. But whatever it is, much more is crumbling in Havana than the streets leading from the baseball stadium to the slums of the city centre, past huge, stylised portraits of Che Guevara, unsullied icon of a dream, and the purity of the dream that was.

The road leads past some of the most outrageously fine, now crumbling, constructions of the Spanish colonial enterprise. Every doorway, however, teems with human life; every window frames a face or cluster of faces, every other hallway broadcasts the libidinous pounding of salsa on to the street; a wall between a home and the thoroughfare is porous in spirit as well as literally. Outside flows an endless river of traffic: vintage American cars, Ladas and creaking bicycles. Women carry their loads, girls display their velvet skin; men gather on corners to chat, boys strut their muscles; the bright fluorescent lights of cafes and bars illuminate noisy card games. Here is Stalinism beneath the palm trees - a crossroads of the senses leading in all directions, towards both hedonism and the austerity of communism; contradictions crashing into one another.

It takes only a short while for the quick-hit façade of sensual exotica to peel along with the plasterwork. Punished by four decades of embargo by the United States, Fidel Castro's island fortress has always needed a patron. And when Cuba lost the Soviet Union in 1991, Fidel Castro exchanged benefactors for the emblem of his arch-enemy: the hated but revered United States dollar. What he got in return was a Time Out guide and a generation of tourists come to gawp and ghoul at Stalinism's last, great exotic failure.

In the Barrio di Colon - the old red-light district in the days of the deposed dictator Batista - a photo shoot is in progress by a Dutch crew armed with lights and reflective shields. Some of the pictures are of picturesque poor children peeping out from cavernous windows, others feature a feline model wearing a summer frock. Surveying this scene is a nuclear physicist called William Rakib, blessed, he thinks, by many visits to the Soviet Union and once charged with a managerial role in Cuba's disastrous nuclear-power programme. 'Capitalism,' he grunts, 'is more toxic than nuclear power'.

To save the quarters of its crumbling capital visible to this new generation of visitors, the Cuban regime has paired up with European governments to restore and rehabilitate buildings that line the Malecon - the ocean promenade - and central boulevards. The sound inside Lorenzo Hernandez's block is therefore an optimistic hammering of nails and whirring of drills; Hernandez, himself an electrician, lends a hand. The exterior of the row of flaking mansions is criss-crossed with wooden scaffolding; the cool, musky stone inside is being damp-proofed, says Hernandez, 'paid for by the Italian government'. A couple of blocks down the prom, however, Lazaro Perez is still waiting for restoration to begin: 'People keep coming from this committee or that, but nothing ever happens,' says Lazaro, who keeps a cow skull on his wall. 'I keep it up there for protection', he explains.

Walk awhile inland, to the once-stately, now ramshackle, San Isidro district around Havana's railway terminus: here, talk of restoration raises a hollow laugh from Mario Vidal, a supermarket security guard who lives with his wife Joania, her father, their six children and three cousins in a cramped one-room flat with raised sleeping space and a small, dark kitchen. Bare wires crawl up the high walls, naked bulbs suspended; pots and pans, flotsam and jetsam, hang from sturdy hooks. 'We eat in shifts,' explains Joania, preparing the first one for her children, including seven-year-old Damien, who suffers from a rare form of meningitis, requiring medicines that can only be bought with dollars. Mario, however, does not like to complain; he wears a smart shirt and pressed trousers, for all the dilapidation around him. 'I've done it up a bit - here, we do our own restoration,' he says. The only problem with living like this, says Miriam Gonzalez downstairs where the dogs bark, 'is privacy. You have to make love while the children are at school'.

As tangerine dawn fades the last stars in Havana's sky, a group of children gather on the cobbles to play a game that enthralls as much as it is simple. With lengths of string, they whip a spinning top, making it dance from stone to stone. They do this, with intensity, for an hour, as morning breaks around them.

The children, in pressed white shirts with red scarves tied neatly round their necks, eventually scuttle off to the call of the bell at Ruben Alvarez school - named, of course, after a revolutionary hero. ' Sin educacion no hay revolucion posible ' declares the sign at the entrance - Without education, revolution is not possible - alongside pictures of Elian Gonzalez restored to his father's loving arms. Head teacher Pilar Mejia explains that curricula are taught in strict accordance with the latest directive from the education ministry, and around five basic principles the first of which stipulates that (she reads, dutifully): 'To love our motherland should be the political goal of the educative process.'

On the wall of the school office, the names of the top and bottom achievers are chalked up on a board. 'We use competition,' says mathematics teacher Rafael More. 'We believe that childhood should be preserved but rigorous; we don't want to exchange what we have for your Nintendo or violent computer games.' Mr More's class - a blend of severity and innocence - bears him out, making most American or British inner-city schools look a little frayed at the edges. Here, there is neither the will nor luxury for relaxation.

This, says William Rakip, the nuclear physicist, is the wheel of revolution that Cuba turns. He insists that 'you do not understand how insurrection is not the same as revolution, it is just a moment. Revolution is all the things that come afterwards.' It's a highly ironic invocation of 'permanent revolution' as advocated by Leon Trotsky, the man Castro's Soviet masters murdered in Mexico City, where Castro and Guevara's insurrection began. But, in Havana, revolution is beginning to look more like stagnation, and the more it does so, the brighter the shine of the glitter across the Straits.

The crusade against the influence of the US has become the work of a network exalted in the folk history of Cuban communism - the 'Committees for the Defence of the Revolution' (or CDR). Hilda Betancourt was there, in 1960, at the giddy moment they were born. She is now CDR co-ordinator for the Dragones district, a lively bustle near the shopping thoroughfare of the old regime; her daughter teaches a salsa class in the adjacent room. 'There was a big meeting in the presidential palace,' she recalls, 'and Fidel said a committee would be set up on each block to defend the revolution. And it's the same now.' The committees are responsible for dragging out the masses for such spontaneous protestations of loyalty as those over Elian Gonzalez, and ensuring that the Commander-in-Chief never speaks to a piazza that is not heaving with crowds. Afterwards, they might conduct a friendly follow-up check on people failing to show up.

The CDR's unbending duty is what Ms Betancourt calls 'revolutionary vigilance. That,' she says, 'is our primary task. At the beginning it was to convince and to watch - and it still is.' Revolutionary vigilance, as one finds out further down the road, means snooping and stalking; and occasionally going on the attack. These are the informers, the political gossips, the eyes and ears of the secret police, foot soldiers of Cuba's keystone KGB, who work in exotica's shadow.

You can hear the drums from the street, starting around sundown on a humid Tuesday, coming now from a building once so grand the French used it as an embassy. The old creaking lift arrives at the door to the top-floor apartment, upon which is written: 'Whosoever enters does so in the spirit of God and Jesus Christ. If not, do not enter.' Miriam Fuerte answers, holding her cigar. There is pure mischief behind her smile; the mischief of magic, for Jesus is not the only divinity present in this place, despite the fact that Our Lady of Guadeloupe in Mexico is looking down from a wall.

Miriam, confident with her wholesome hips, begins the Dance of the Walking Dead, that of the Santeria God Babalaye. The essence of Santeria is that it is the African religion of the slaves upon which the Roman Catholic faith was superimposed: 'The slaves were not allowed to celebrate their saints,' explains the Santeria priestess, 'so they went to Catholic church and did so under other names.' For this reason, each Santeria deity has a second, Catholic, face. Babalaye's is that of Lazarus, raised by Christ from the dead. 'He,' says Mercedes Veida, as she prepares to join the dance, 'is the most important of them all.' Mercedes intoxicates herself gradually with the rhythm of the drums. Fumes of tobacco and sickly sweet aftershave fill the room. Her eyes grow larger than should be possible as she looks both inward and outward, now on the parquet, now up again, possessed.

When it is over, Miriam blows a bonfire of cigar smoke and beams a huge grin before admitting visitors into her consulting room, her chapel, 'my fortress'. People come here 'from the factories, streets and stores,' explains Miriam, 'for healing of illness and tribulation'. The altar is a jumble of objects, charged with meaning. Bowls of putrid water, a plastic toy kit of a Soviet bomber, lamps, jars, candles, old bottles. Eleggua - 'He who Opens and Closes the Roads' is a doll who controls destiny and whose Catholic face is The Holy Child of Atocha. Especially lovely is Ochun (here, a pineapple-shaped vase), goddess of 'love, sexuality and coquettishness' - to Cuban Catholics Our Lady of Charity at Cobre.

Miriam used to work, she explains, for Che Guevara in the Ministry of Industry. She has his portrait on her bedroom wall. 'It has a positive force,' she says. 'I used to see him most mornings in the office,' and for all his Marxist beliefs, 'I observed and understood that he was a man of great light who, when he died, gave much energy to the world.'

'Feeling dull but dutiful,' wrote the great journalist Martha Gellhorn, 'I went to look at Alamar - a big housing estate with rectangular factories for living spread over the green land off the highway outside of Havana.' Why try to improve on Martha Gellhorn? Alamar was also known as 'Little Russia', since it was in part built for Soviet technicians, in a Lego-brick style that would make them feel at home, a sort of tropical Smolensk-sur-Mer.

Isadoria Castaneda's block, however, was built by her husband's own hand under a deal whereby selected workers could construct their habitation during what was called the 'Special Period' of shortage and deprivation after the Soviets left. Mr Castaneda sailed on an industrial factory-fishing ship before building Edificio No 53, and Isadoria earns a pittance training as medical technician. She is dumbstruck to have two people in her home with connections to Liverpool: 'Wait till I tell my daughter that people came here from the same city as the Beatles! She won't believe it! I know all their songs - "Penny Lane", "Submarino Amarillo".'

But then Isadoria performs some mental acrobatics between her two great loves - the band and her government. 'If the government banned the Beatles, I would still love them anyway. But I would love the government, too. I don't see any contradiction in that. The visiting Beatles fans do not understand. 'Did your mother not make you do things?' retorts Isadoria, 'Of course she did. And you still love her, don't you?'

Alamar's living factories get progressively tattier as they approach the coast and the outdoor 'Playita' - Little Beach bar. There is in fact no beach, but there is pleasantly chilled Cristal beer served by pleasantly hospitable Joely Garcia, who does not equate the Cuban government with her mother. Joely wants to know about the attack against New York on 11 September. 'We never hear about the American people, only about bad guys and politics.' She wants to travel, 'but I can't even go to the tourist hotels in my own country. I don't like to go to the crowded beach and look through a fence at foreigners on theirs.' The system of entitlement to food rations, which enables Cubans to eat, provides for, says Joely 'eight eggs a month. That's four omelettes. If you go to the dollar store for nice food, you spend a month's salary on a single trip.'

Friday night is music night all over Havana, no matter which kind you like. Salsa rules the night air, but traditional folk ' son ' remains. Rap makes inroads, and not without political implications. But the one brand of music that has survived and will always survive Cuba's changes, come what may, is jazz, standing as it does, like Cuba, at the crossroads. 'This is where all styles meet,' says Pedro Gonzalez Sanchez, who has been playing the bass for nearly half a century. When Pedro was eight he shined shoes in old Havana - American shoes, rich Cuban shoes. His father was a drummer, his grandfather a pianist. Pedro started to play, too, '10 to 12 hours a day, at home; when I wasn't playing I was listening'. Revolution came, and musicians adapted. ' C'est la vie, monsieur ,' he beams.

The principal advantage was a system of scholarships to the music academies, 'which made jazz more sophisticated'. In 1981, Pedro played bass in the first Cuban band since the communists took power to visit Britain - Pepin Voyante, as proudly reported in the Morning Star .

But tonight it is Pedro's son, Omar, who takes the stage at the Jazz Club downtown. Omar played piano in a band with his father until interrupted by military service. But there was always the military band, in which he was assigned the tuba. 'I used to march up and down playing a nice bluesy sound on that tuba,' he grins. Omar found his first bass, 'busted up', in a military store; he helped himself, then taught himself. 'I practised while everyone slept in the barracks; playing all night.'

In the new Cuban order, Pedro plays to matinee audiences paying in pesos and evening ones who do so in dollars. Tonight is his big opportunity - invited by saxophonist Javier Zalba Suarez and pianist Gilberto Fonseca into the musical top drawer. Suarez learnt his craft from the CIA - 'listening to John Coltrane and Charlie Parker on Voice of America radio,' he says. 'But we used to add our own sound, "Cubop", with an Afro-Cuban flavour. Here, we have no school of jazz, this is God's own jazz country.'

If there is a trinity of clichés that brands Cuba, it is communism, cigars and libido. This third is nothing new, but it, too, has themes and variations. Sex walks the streets of Havana. Castro promised to liberate Cuba from its role as America's brothel. But by reintroducing the dollar, he has turned it into the boudoir for a new generation of clients from Europe, Canada and South America. Thousands of Havana's girls and women are for rent - by the hour, day, even by the week.

Two in the morning, and the Parque Central is emptying out, but Mileydis Padrino Diaz is still on her patch, escorted by two gentlemen. One of them makes the approach, describing himself as 'a lawyer'. Milyedis, with braided hair and jeans, smiles bittersweetly. Ten dollars for the chica, plus another 10 for la casa - 12 quid the package.

Quickly down the street off the square and suddenly a dark alleyway between two cliffs of stone - retailers, customer and commodity. An old bucket gets knocked over, a cat objects; knock-knock on a door, a woman beckons us in, shakes hands like the hostess at cocktail party, takes the $20 and gestures towards a ladder leading to an overhang beneath which she watches television. Milyedis smiles again and follows up the ladder. On the shelf is a bed; Milyedis draws the curtain and starts to unpeel.

When motioned to stop, she asks, 'Are you timido ?' Milyedis has been doing this for 'about two years. For my mother'. That's Mama downstairs? 'Yes... father left for Miami, we've heard nothing of him.' The audience laughs on the variety show beneath. Milyedis has given up think ing too hard about her work, but not about her corroded life. 'No, I don't hate the customers any more. I did at first... hey, why ask these things? I want to do something that makes me happy - maybe be a model.' Time to go, and let Milyedis get on. Back down the ladder, so soon, to Mother's bewilderment. 'Thank you, señor,' says the woman, patting Mileydis on the head. 'She's only my little baby.'

Where there is degradation, there is usually an attempt at redemption. Those loyal to the Cuban regime, like the nuclear physicist William Rakip, insist that there is no democratic underground or opposition in Cuba. 'They just want to go to the US Interest Section,' he says, 'and get a visa for Miami.' So what about Elizardo Sanchez - the man who met with Spanish Prime Minister Felipe Gonzalez when he came to Havana for the Hispanic Summit in 2000? 'He is an extreme right-winger,' says Rakip, 'who just wants to go to Florida. He has no credibility.'

On the wall of Sanchez's front room hang photographs of him shaking the hands of Gonzalez, Vaclav Havel, Jimmy Carter and Teddy Kennedy - 'no credibility'. Sanchez, it turns out, was a senior member of the Popular Socialist Party who fought with the revolution. 'Maybe I made a mistake back then, but that's the way I am,' he laughs, 'and it's too late to change now.' Sanchez broke with Castro in 1967 to found the Left Opposition, inspired by the Trotskyite ideas of Jacek Kuron and Karol Modzelewski in Poland. In 1972, he was jailed for two years for criticising the secret police, then again in 1980: this time an eight-and-a-half-year term for possessing 'enemy propaganda' - ie keeping Kuron's and Modzelewski's books in the library at Havana University, where he was a professor of philosophy.

'Two days after I left prison I received two journalists at my house and told them about what I saw in Cuban jails. For that I was jailed again.' Sanchez now lives under unpleasant circum stances in a pleasant street: 'This house has been ransacked 10 times; they throw stones; we can't have offices or a photocopier, we have to work out of our houses - and it's hard for our families.

'This is,' he says, 'a tropical model of totalitarianism - to a degree like the Eastern European models, but here established on the shoulders of a popular revolution, not by the tanks of the Red Army.' The repression, he says, 'is not comparable to the USSR, or Haiti or the mountains of Bolivia, but it denies freedom of expression, association, of the press, of movement of the right to form political parties or establish a business.'

Up until 1988, says Sanchez, 'the government didn't think the dissident movement was worth noticing. But, silently, the human rights movement grew. In the old days, we were a sapling in its back garden, and now that we're a tree, the government cannot pull us up by the roots. They've come to realise they cannot keep control. There are no death squads or disappearances...' he continues, with a scornful laugh, 'and so, instead, we have become a country of prisons and prison camps - as many as 400 or 500 across the nation.'

Then Sanchez steers the conversation towards the conclusion he sees fit: 'I am not the most dangerous man to this regime,' he says. 'A real opposition leader is emerging and you must visit him.' From the leafy streets, then, out into the working- class suburb of Cerro, one of the poorest and most remarkable of Havana. The crowds on the narrow streets are as thick as the air.

Oswaldo Paya is late for our appointment at his home because he has been called away on an emergency; a generator has broken at the hospital and his skills as an electrician are needed. So there's a wait, beneath his large picture of the Sacred Heart. Finally he returns, apologising and out of breath.

What is it about people like this that mixes pride and humility, which in turn itself humbles? How can they be so simultaneously bold and timid? They have eyes full of both the sorrow of experience and the hope of their convictions. They 'live to the point of tears', as Albert Camus wrote, but then wipe them away.

Paya has mounted potentially the most effective challenge to the Cuban regime since its foundation, because he is calling its bluff on its own terrain. He has devised a campaign called 'Proyecto Varela', a petition for democratic change collated under Articles 63 and 88 of the Cuban constitution, which guarantee that if 10,000 signatures are gathered in support of a series of demands, its motion must be put to referendum. The Proyecto Varela contains five such demands: 1. Freedom of association, speech and the press; 2. Liberation of political prisoners; 3. The right to sell labour freely and establish businesses; 4. The right to present candidates for election; 5. Free elections within a year if the referendum is successful. In short, the end of Cuban communism.

'A lot of people speak for Cuba and the Cubans,' says Paya, 'but the Cubans never get to speak for them selves. This is an attempt to do this, through the ballot box. In December, we passed the 10,000 mark easily, but discovered the Communist party had entered forged names to discredit us. So now we're going round each signatory to make sure this is them, and their ID number on the sheet they signed. The authorities have started to arrest some of our activists and seized some signatures, but we still have 10,000 - this is what matters.'

Paya kneads his hands. He has a boyish face and a mop of curly dark hair. 'Oh, all these tourists come here,' he reflects, 'but what do they see? They come here to enjoy themselves in a place where the Cubans are discriminated against, a kind of apartheid. We want them to see that this is a sick society, where people have lost sense of who they are, and who have lost faith.'

Mr Paya's faith gives him that extra notch of strength that one recognises from people like Martin Luther King. He likens his movement to that of the early revolutionary Christians. 'I grew up during the period of religious persecution,' recalls Paya, 'when I was 17 years old they sent me to a labour camp for three years, breaking stones. 'So this is political,' says Paya of his movement, 'but there's a human and spiritual dimension for me. For me, this is about liberation - liberation from fear.'

Lazaro Vargas steps up to Home Plate. The game is a stroll through the furnace of the night: at the top of the fifth inning, Industriales are romping towards an 10-1 massacre. He drives a lusty curveball past second base, for a single - for love, for glory, for Cuba. On the concrete steps, the crowd dance and sing. They love Lazaro Vardes with all their warm Cuban hearts. But they do not share his love for the Cuban order of things. Here, they are not intimidated by fear, nor are they charged by Oswaldo Paya's faith so much as by carefree defiance.

'Fidel?' says Mamlene, an

auto worker, 'he's too old to fuck now, so he takes it out on us.' 'Fidel!

Fidel!' shouts Manuel, holding his palms aloft as though to hail the

Commander-in-Chief at a rally in the Plaza de la Revolucion, 'Oh, Fidel!' Then

he whips the left palm behind him and, with a puckish grin, oozing mischief,

makes to wipe his backside.

People's revolt challenges

Castro

Ed Vulliamy in New York

Sunday May 12, 2002

The Observer

Fidel Castro faces the most serious non-violent challenge

to four decades of communist rule in Cuba in the form of 11,000 signatures

demanding democratic reform.

The petition - the Varela Project, named after Felix Varela, a priest and hero of Cuban independence - was collected by a loose organisation put together by the man emerging as Cuba's most effective grassroots opposition leader, Oswaldo Paya, an electrician from a Havana shanty town.

The campaign is seen as the biggest home-grown effort to push for reforms in Cuba's one-party system.

Presented to the National Assembly on Friday, the petition proposes a referendum asking voters if they favour civil liberties such as freedom of speech and assembly, and amnesty for political prisoners. The move came two days before the arrival of former US President Jimmy Carter, who is expected to urge democratic reforms.

Paya, who gives his first major interview in today's issue of the Observer Magazine, devised a way of challenging the Cuban system from within: two articles in Fidel Castro's own constitution providing that if 10,000 signatures can be gathered around any demand or set of demands, it must be put to referendum.

In 1996, the Varela Project duly set about collecting names to back five essential demands, for freedom of expression and association, free and fair elections in a multi-party system and an economy incorporating 'private, individual and co-operative enterprises' observing 'the rights of citizens and workers' - in effect, the end of communism in Cuba. One clause demands that the rest become law should they be carried in the vote.

'A lot of people speak for Cuba and the Cubans,' Paya told The Observer, 'but the Cubans never get to speak for themselves. This is an attempt to do this, through the ballot box... We are asking that the Cuban people be given a voice in a popular vote, so that the sovereign people are those that decide to begin change for the good of our children.'

Paya, who lives in

the peeling rococo suburb of Cerro, calls himself a 'Christian Humanist', and

has his political origins in the radical Christian Liberation Movement - akin to

the Solidarity movement in Poland - which operated underground in Cuba, rather

than join rightwing emigrés across the Florida straits in Miami. As a young

activist, he served a sentence in a military labour camp.

Fidel's parting shot

Next month, Fidel Castro

turns 75. He has promoted a communist Eden in Cuba, but when the legend is dead,

will the revolution outlive the man?

Cuba after Castro - Observer

special

Ronan Bennett

Sunday July 29, 2001

The Observer

At 75, Fidel Castro is sick and grey, a visibly failing

figure. Rumours of serious illness - heart trouble, brain tumour, Parkinson's,

take your pick - have been gathering momentum for more than a decade. The Cuban

authorities have always played them down, but they could hardly discount

Castro's recent televised collapse. Like the man, the regime Castro put in place

more than 40 years ago, admired and loathed in equal measure and with equal

passion, has looked shaky for some time. Not just shaky, Castro's critics would

say, but as sick and grey as its creator, and they gleefully predict that with

the demise of the man will come the collapse of the Cuba he made. They may be

right. On the other hand, the Cuban leader has spent a lifetime confounding

expectations.

Nothing about Castro has been ordinary or expected; he is a man to whom the normal rules do not apply. In 1955, as an exile in Mexico, the 29-year-old Castro publicly vowed to lead an invasion of Cuba to overthrow the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista. He was scolded by General Alberto Bayo, who was then training the guerrillas Castro would take with him: 'Don't you know that a cardinal military principle is to keep your intentions secret from your enemy?' Castro is said to have replied breezily: 'It is a peculiarity all my own.'

Castro's peculiarities are legion: monumental and, at times, bombastic self-belief is one of the more obvious. It's easy for his many enemies to portray this as buffoonery, as delusional and empty, but it has seen Castro through a host of obstacles that would have defeated a lesser man, and it has been central to Cuba's continuing struggle with the United States, the superpower neighbour that has borne the island and its six million people little goodwill for more than a century.

Wedded to the self-belief is an extraordinary and apparently invincible sense of optimism, important for the same reasons. When Castro's guerrillas (82-strong) reached the Cuban coast at Las Coloradas on 2 December 1956, their rusting tub, the Granma, foundered in storms on the rocky shoreline. The exhausted guerrillas scrambled ashore, losing equipment and arms, and began a horrific trek through stinking mangrove swamps, all the while harried by Batista's airforce and pursued by army units.

Ambushed three days later at Alegría de Pío, more than half the guerrillas were captured or executed. The survivors scattered. A handful, including Castro, his younger brother, Raúl, and his close friend, Che Guevara, reunited in the foothills of the Sierra Maestra. At this point, the guerrilla army with which Castro proposed to overthrow the dictatorship consisted of no more than a dozen fighters and seven weapons, and they were surrounded by Batista's troops. By any normal standards, the landing had been a disaster. But Castro was elated. Looking over the weary, wounded stragglers, he declared: 'The revolution has triumphed.'

Few would have given him any chance of success, and Batista declared on radio that Castro was among the dead. Yet little more than two years later, Batista was on his way into exile and, amid euphoric popular demonstrations, Castro and his 'barbudos' (bearded ones) swept magnificently into Havana. In achieving power, Castro defied all the normal rules. To maintain it, he would continue to defy them for the next 40 years.

Fidel Castro was born on 13 August 1926 on a sugarcane and cattle plantation near Birán, on the island's northern coast, owned by his father, Angel, a tough, no-nonsense self-made man originally from Galicia in Spain. Castro's upbringing was comfortable, in contrast to the poverty of most of the region's inhabitants. He says he was aware from an early age of his relative advantages, noting that he and his eight siblings did not go barefoot like the other children. In a candid interview in 1959 with his friend and collaborator, Carlos Franqui, then editor of Revolución , Castro says he was a strong-willed and rebellious boy, especially with teachers who attempted to use force. The Franqui interview apart, Castro has said little about his private life or family; most of what is known of his personal habits comes from family members, including a sister, a daughter and a number of ex-lovers, who have defected to the US.

An important influence on the young Fidel was the semi-mythic figure of José Martí, the Cuban poet and independence leader who rose against the Spanish occupiers and was killed in battle in 1895. Martí, revered as an idealist who gave his life for his country, inspired Castro's generation. For them, the independence won in 1902 was a sham concocted by the Americans, who maintained a stranglehold over post-independence economic and political life, turning Cuba into an American colony in all but name.

By the 1940s, when Castro was a student at Havana University, anti-American feeling was strong; young people looked back to Martí's example of heroic self-sacrifice, and they looked forward for a leader who would deliver them.Cuban politics at this time resembled Irish politics prior to the 1916 rising. In both countries, passions ran high. There was popular antipathy for foreign manipulation, but some benefited from the relationship. And, as in Ireland, Cuban politics were never simply a matter of voting; the gun was very much part of the process, with political parties maintaining links with gunmen who would occasionally step out of the shadows to intimidate or assassinate rivals.

Castro, drawn to the nationalist Ortodoxo Party, so-called for its loyalty to the principles of Martí, does not deny he carried a revolver during his five years as a law student. What he has denied is Batista's claim, never convincingly prosecuted, that he killed two men during his student days. No evidence has ever been adduced for this, or for the more spectacular allegation that during the bloody rioting in the Colombian capital of Bogotá in 1948 he killed up to six priests. Nevertheless, the Castro who emerged on the radical fringes of Cuban politics in the later 1940s was rebellious, tough and determined, a street-fighter more than capable of standing his ground against equally tough opponents. As yet, however, he was still without a focus for his formidable energies, political ambitions and already highly developed sense of personal destiny.

That focus emerged in March 1952 when Fulgencio Batista, with army backing, launched his palace coup. Such was the fragmentation of the political parties that they were unable to mount any effective challenge. With democratic politics at an end, Castro set about planning an armed uprising to galvanise resistance. 'This was not a political situation,' Castro was to say later. 'This was a revolutionary situation.'

The assault on the Moncada Barracks in Santiago is pure Fidel. His followers, who included Raúl, were all under 30, none had any serious military experience, most were middle-class university graduates. Like the doomed Easter Rising in Ireland, it was quixotic, epic, tragic and, like the Easter Rising, it was in its very failure that the seeds of a later, hard-fought victory were sown.

The surprise attack took place at dawn on 26 July 1953. It was a daring conception. The idea was for Fidel's 130-odd force to bluff their way into the barracks, overpower the 1,000-strong garrison, seize the armoury and distribute the weapons to the crowds that would turn up in support. In the event, the poorly armed attackers were quickly rumbled and once the alarm was raised were easily outfought. At least 68 of the Fidelistas were tortured and executed, and most of the rest rounded up and put on trial.

Castro was lucky to survive - his fair share of luck has over the years undoubtedly strengthened his sense of destiny - and only did so because he was caught by a humane officer who ignored orders to summarily execute prisoners. Defending himself in court, Castro remained defiant in defeat. 'History will absolve me,' he declared. His steadfastness earned much admiration. He was in the tradition of his hero, Martí, a failure but a romantic, even if the romance was always centred on himself.

The Irish revolutionaries who took on the British in 1916 revised their tactics in prison. So did Castro, whose natural robust health, energy and irrepressible spirit ensured he fared well in jail. He developed a guerrilla strategy: a few armed men in the mountains would engage the army in small-scale actions, recruit local peasants, receive arms and supplies from supporters in the towns, and gradually build up their forces until they were strong enough to break out of the mountains and march on the cities. Castro got his chance to put the theory into practice when he and his followers were unexpectedly released from prison and sent into exile.

Arriving in Mexico City in the summer of 1955, Castro was introduced to a young Argentine doctor, Ernesto (Che) Guevara. From the beginning, there was extraordinary mutual appreciation. 'This is someone I could really go all out for,' an excited Guevara told his Peruvian wife, Hilda Gadea. Gadea, like her husband already a convinced Marxist, thought Castro, with his short, curly hair, carefully trimmed moustache and dark suit, looked like a bourgeois tourist, but she, like Che, saw that beneath the outward appearance was the genuine article, a man who not only preached revolution but had taken up arms in its cause.

Nevertheless, there is a telling contrast in the outward appearance of Fidel and Che. In a photograph taken in 1956, when the two men were briefly detained in a Mexican prison at the behest of Batista, we see a bohemian Che, bare-chested and hair-tousled, his white trunks visible at the top of his casual trousers, belt undone, while Fidel, carefully groomed and dressed in shirt and tie and polished shoes, is buttoning up his jacket as if going off for a business appointment. It is not hard to guess from the picture which man would go on to make the politician and which the eternal revolutionary.

If Guevara found in Castro a man worthy of his allegiance, a man he could follow to the end, Castro found in the Argentine a comrade of genuinely and deeply felt radical beliefs. In time, Guevara's political influence, along with Raúl's, would be important in pushing Castro to the left. The debate over Castro's communism - crucially, at what point he became a communist - still rages. It seems unlikely that the uncompromising Guevara, who was nothing if not demanding in his political friendships, would have formed such a close bond had he not been convinced of Castro's left radicalism.

Yet there is nothing in Castro's public statements or in the manifestos of his 26th July Movement (after the date of the Moncada assault), with their vague promises of land reform, justice, and jobs for all, to suggest that he wanted to establish communism in Cuba. Nor was his relationship with the Communist Party of Cuba close; communist leaders were to remain highly critical of Castro's 'adventurism' for some time.

It may well be that when he and his 81 comrades set sail in the Granma, Castro was what he still claimed to be - a man of the democratic left who wanted to free his country from the evils of domestic dictatorship, foreign intervention and mass impoverishment, and was prepared to work with other groups to achieve that end. But, of course, political ideas change direction, and once the bullets start flying they rarely turn to the right.

Though now thoroughly mythologised, Castro's campaign in the Sierra Maestra was, for the most part, a series of messy, small-scale encounters, rarely involving more than 100 combatants on either side and usually many fewer. It is unlikely that the total number of dead reached 1,000. Batista's much better equipped army should have been able to contain the guerrilla threat. That it did not was due to the army's demoralisation and incompetence, to the rebels' tenacity and to growing popular unrest, strikes and organised resistance in the cities. But Fidel's indomitable personality was also crucial.

The Sierra saw Castro at his best. Like Shackleton, he kept private doubts to himself, aware that the slightest hint of demoralisation in the leader could have disastrous consequences for those he commanded. He was courageous in battle, leading from the front, and was a shrewd judge of character.

He also had the showman's instinct for propaganda. At one point, he arranged for the veteran New York Times journalist Herbert L. Matthews to be smuggled into the Sierra Maestra and hoodwinked Matthews into thinking the rebel forces were numerous and well armed. In fact, they were starving, with uniforms little better than rags, and had few serviceable weapons. Castro arranged for 'runners' to interrupt his interview with Matthews with urgent battle reports from fictitious rebel columns, and the men borrowed each other's weapons and shirts to give the impression of well-clad numbers. Matthews wrote up his scoop, and the Castro legend was born.

Gradually, as Castro had predicted, the rebels won over much of the peasantry, attracted recruits, and grew in confidence and strengh until, in August 1958, Castro dispatched columns under Guevara and Camilo Cienfuegos to begin a march on the towns. Guevara's successful attack on the strategically important town of Santa Clara four months later effectively brought victory to the rebel army. Batista packed his bags and fled on New Year's Day.

Every revolution has its heroic phase and this was it. A starburst of violence and generosity, unqualified promises, delirium, idolisation, and general craziness. Then comes the reality. In Cuba, it fell hard. Castro's triumphal entry into Havana in January 1959, after barely two years in the mountains, set up impossible expectations. But Castro and his 'barbudos' were immediately confronted with a staggering array of problems. Many of those belonging to rival political organisations, who had played a part - often underestimated by the regime's historians - in toppling Batista, resented their displacement by the 26th July Movement and started to conspire against the new regime; landowners, businessmen and the middle classes (including one of Castro's sisters and his mother) were outraged by land reforms and the confiscation of the large estates (including the Castro estate). The economy, chiefly reliant on the sugar harvest, was in crisis; there were scores to be settled with, as Guevara put it, the eye-gougers, the castrators and the torturers of the Batista dictatorship (the executions, presided over by Guevara, were brought to a halt after international protests).

And then there were the Americans. Although Castro visited New York soon after taking power in an attempt to win over American opinion, Washington wrote him off as a communist troublemaker and has never forgiven him for refusing to bow down and say 'Uncle'. The CIA organised numerous acts of sabotage, including blowing up a ship in Havana harbour with huge loss of civilian life, assassination attempts, and, of course, the infamous Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961. When these failed to bring Castro down, the Americans embarked on a vindictive campaign of economic embargoes. The US actions had the effect of polarising Cuban society and increasing the internal repression which has been one of the more distasteful aspects of the regime.

Rebuffed by the West, Castro, with the active encouragement of Guevara and Raúl, and the now supportive Communist Party of Cuba, had little choice but to turn to the East. This led, in 1962, to a rare tactical blunder when Castro allowed the Russians to establish missile bases in Cuba. President Kennedy's ultimatum that they be dismantled brought the world to the brink of nuclear catastrophe. Castro and the Russians were forced into a humiliating climbdown.

It was Castro rather than Guevara who proved able to come to terms with the realpolitik of the post-missile crisis years as relations with the Soviet Union settled (the Russians effectively bankrolled the Cuban economy until 1989, providing Cuba with oil and with markets for her sugar). By the mid-1960s, Guevara, who had been minister for industries and head of the national bank, had to admit he had failed to achieve his ideal of a communist Utopia in which greed and selfishness were banished and all cherished notions of sacrifice and solidarity.

Fidel, by far the more pragmatic man, had different targets and he has been extraordinarily successful in achieving these. In spite of the difficulties created by the US embargo and the loss of subsidies from the Soviet Union, the Cuban education and health care systems are still superior to those of the rest of the region; to be poor and sick in Cuba is infinitely preferable to being poor and sick in Guatemala or Honduras.

By the time Guevara left for his doomed expedition to Bolivia in 1966, he was already an anachronism in Cuba. And Castro knew it. Unwilling to modify the ideals of the Sierra Maestra to the realities of day-to-day government, Guevara had no place in the ruling circle. He couldn't stay, but, Castro knew, if he went he would probably be killed. There have been suggestions that the two men argued after a particularly uncompromising speech by Guevara, but if so it does not seem to have dented their personal affection for each other. When Castro visited Guevara's training camp shortly before the expedition got under way, the two men spoke fondly together. After they separated, witnesses observed Castro sitting alone, shoulders slumped, head in his hands. They thought he was crying.

Guevara's death in Bolivia the following year marks an important turning point in the Cuban Revolution and in Castro's own story. From then on, Castro, the man photographed in his Mexican prison cell wearing shirt and tie, polished shoes and dark jacket, may have swapped this more conventional politician's garb for the guerrilla's olive-green uniform, a reminder of the high idealism of the Sierra Maestra, but he made the leap that Guevara could not make of going from opposition to office.

A politician of acute tactical and strategic abilities, he will have read his political obituary a thousand times. Many expected him to fall after the collapse of the Soviet Union, when the Cuban economy was plunged into its worst ever crisis. The regime overcame this by liberalising the economy and by encouraging foreign tourism. Against the odds, Castro survived, battling against saboteurs, assassins, dissidents, embargoes and trade restrictions, and the implacable enmity of Cuba's powerful northern neighbour.

Many of those who have predicted his demise have been bewildered by his political longevity, often because they underestimated his popular support. That support has been said to be falling for more than 40 years now, yet still Castro hangs on.

When he goes it is likely to be on his own terms. Fidel's extraordinary personality has shaped modern Cuba. With his departure, the question will be whether the Cuba he created can survive without him. De Gaulle used the threat of 'Après moi, le deluge', not just as a political tactic but to stake his claim for posterity. For the same reason, Castro must be hoping that after him, the floods hold off.

Ronan Bennett,

a distinguised novelist and screenwriter, is currently writing a film script on

Che Guevara and the Cuban revolution for Picture Palace/FilmFour

The Castro years: the key

events

Cuba

after Castro: Observer special

Sunday July 29, 2001

The Observer

Aug 13 1926: Fidel Castro Ruz born in Biran, Eastern Cuba.

July 26 1953: Castro launches armed struggle against Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista. But attack on Moncada Barracks fails.

Sept 1953: Castro is sentenced to fifteen years, making famous 'history will absolve me' speech from the dock.

May 1955: Batista grants amnesty to Castro, who goes to Mexico to plot invasion of Cuba.

Dec 2 1956: Castro and 82 other rebels land at Playa Las Coloradas in Granma yacht. Cuban army easily outnumbers and rout rebels, but survivors take refuge in Sierra Maestra mountains and launch guerrilla war.

Dec 28 1958: Fall of Santa Clara, after rebel attack led by Che Guevara. Batista troops end military resistance.

Jan 1 1959: Batista flees to

Dominican Republic as the rebels take power.

Castro's men

pour into Havana

Angry young

Cubans take over

Jan 8 1959: Castro enters Havana following triumphant procession through island from east of Cuba. Fidel Castro: 1959 profile

Oct 19 1960: United States begins partial economic embargo.

Jan 3 1961: Washington breaks off diplomatic relations with Cuba.

April 16 1961: Castro declares Cuba a socialist state.

April 19 1961: Bay of Pigs invasion. CIA-backed Cuban exiles are defeated.

Feb 7 1962: United States imposes full trade embargo on Cuba.

Oct 1962: Cuban Missile

Crisis. After thirteen day stand-off, Russians withdraw missiles from Cuba.

Observer

leader: a chance to save the world

Oct 9 1967: Che Guevara killed by Bolivian troops seeking to emulate Cuban- style revolution in South America.

Sept 1 1977: Resumption of limited economic ties between Cuba and United States.

Apr-Sept 1980: 'Mariel Boatlift'. Cuba allows mass exodus of about 125,000 citizens to the United States, many leaving from the Mariel port west of Havana.

Aug 14 1993: Havana ends ban on use of dollars.

Aug 1994: Raft Crisis. More than 30,000 Cubans flee island on flimsy boats, many perishing in shark-infested waters between Cuba and Florida. Washington and Havana sign migration agreement to stem exodus and allow minimum of 20,000 legal entry visas per year for Cubans.

March 12 1996: The Helms- Burton law - allowing the United States to penalise foreign companies investing in Cuba - is signed into law by President Clinton.

Jan. 21-25 1998: Visit of Pope John Paul II, who condemns the US embargo and calls for greater freedom on the island.

Jan 1 1999: Castro celebrates 40 years in power.

Nov 1999 - April 2000: Elian Gonzalez affair dominates Cuba-US relations. Elian is eventually returned to his father in Havana.

Rafael

Garcia-Navarro on the Elian affair

Ed Vulliamy:

A conflict that belongs to history

Elian seized

at gun-point

June 25 2001: Castro has to be helped off stage after near collapse at open-air rally outside Havana

July 27 2001: Castro leads crowd, estimated at 1.2 million, in parade to celebrate the Cuban revolution and demonstrate against the US blockade. Castro prepares to celebrate 75th birthday in August.

Fidel Castro

|

Many happy returns of the

day to the Cuban leader Fidel Castro, who is 75 today.

Here's our guide to the best of the scourge of the US

on the web

Ashley Davies

|

|

1. Many 75-year-olds are happy to accept a pension after a life of hard work, but not Mr Castro, who is steadfastly holding on to the communist regime he helped form.

2. But the cigar-chomper has been getting a bit wobbly of late. He recently fainted during a televised speech. He returned after 10 minutes to say he was very tired, but not to worry. It was just that he hadn't slept that night.

3. Still, he is rumoured to have been losing weight faster than Geri Halliwell.

4. But Castro is made of strong stuff. Something of a Latino Rasputin, there have been dozens of attempts on his life. The CIA reportedly tried to humiliate him by putting thallium salts into his shoes to make all his hair fall out. There was also an embarrassing plan to kill him with an exploding conch shell.

5. A devout Communist, mischievous cynics reckon he is worth $100m. But he says this is rubbish, claiming no one in his family has a dollar account outside Cuba.

6. Nevertheless, he has influential friends and has been known to enjoy a round of golf with the Latin American guerrilla leader and hero to 1960s radicals, Che Guevara. Lenin would have been proud.

7. In his youth, Castro was something of an athlete.

8. He first came to political prominence when he led an attack on the Moncada army barracks in 1953. It failed, and nearly all his men were killed or captured. At his trial he made his famous "history will absolve me" speech.

9. After two years in jail, followed by several years of guerrilla warfare, he became president of Cuba in 1959.

10. Unkind people say

"you know

you're in trouble

when the leader of your country wears a uniform".

Fidel Castro is no Santa

Claus

Gerry Adams and the Left conveniently forget

the truth about Cuba's oppressive regime

Cuba after Castro: Observer

special

Henry McDonald

Sunday December 23, 2001

The Observer

Fidel Castro is a kind of secular Santa Claus for the Irish Left. Bearded,

cuddly and grandfatherly, El Commandante is as important a myth for Marxists as

Father Christmas is for children. Like the man with the big white beard, red

fur-lined suit and black sack, Irish leftism's factions want to believe that

their icon, and more importantly the ideology he embodies, actually exists. And

when they catch a glimpse of the political version of the toys hidden in the

attic or the wardrobe - in Cuba's case, the hundreds of political prisoners, the

thousands upon thousands of exiles - the true believers turn a blind eye lest

such a sight might shatter their illusions.

Gerry Adams has just been to Santa Castro's grotto where he asked for a socialist republic, a free health service and even a request that his fellow bearded one slide down the chimneys of west Belfast for a visit. Whether he gets any of these things for Christmases present or future is doubtful given that his party first has to administer Stormont rule in Belfast while one of its Ministers tries vainly to save the NHS in Northern Ireland from breaking apart. Perhaps though his third request may yet be fulfilled if the Cuban people ever get the chance to elect their leaders and decide to send Castro packing.

One of the most disturbing aspects of the coverage of Adams's trip has been the lack of criticism in the Irish media of Castro's one-party state. It has always been hipper to throw your arms around Fidel than some of his old comrades such as East German despot Erich Honecker or the Czech tyrant Gustav Husak. Unlike the grey men of the eastern European politburos, that combination of rum, cigars, sand and sun always gave Castro's brand of totalitarianism a sort of sexy quality.

The problem is the only sex that counts on the island today is the cheap kind that predatory Westerners pay for in dollars and pairs of Levis. Cuba has become a magnet for sex tourism. In their quest to survive the cruel, idiotic, counter-productive American trade embargo, the Cuban regime has allowed tourists' haunts to become sexploitation centres.

Cuba now resembles China, socialist only in name, run on Leninist-capitalist lines, combining the free market with a distinctly unfree one-party political system. Terrorists such as members of the ETA murder gang are harboured, eluding justice back in Spain. Meanwhile more than 300 dissidents including trade unionists and writers are interned in prison camps simply for their beliefs, according to Amnesty International. Astonishingly, the Irish media touched on none of the regime's nasty aspects during Adams's trip to Castro's grotty grotto.

The fact, for instance, that Adams was once an internee, detained without trial, should have prompted reporters to ask for his thoughts about political prisoners in Cuba. That particular subject was not broached because it would have been the equivalent of showing the kids the toys before Christmas Eve, thus exposing the Santa myth.

This diffidence in exposing the dark side of Castro's communism is partially rooted in that very Irish phenomenon of forever siding with the underdog. In the face of a mighty and spiteful neighbour, Cuba clearly is the heroic underdog. America is the villain of the piece, its trade blockade inflicting misery on ordinary Cubans while providing a convenient excuse for the politburo's own failings. Moreover, Cuba's achievements in health and social welfare have been all the more remarkable for that. None the less the one-party system should not be seen as some kind of 'social tax' for those gains.

In the minds of Irish and Western leftists Castro's Cuba evokes images of a world that almost everywhere else on the planet has ceased to exist. The legends of 'socialismo o muerte' and 'Hasta la victoria' alongside the murals of Che, still Christ-like in immortality, re-create a lost Arcadia, as comforting and intellectually soporific as the memories of childhood at Christmas. But in the grown-up adult world reality is always more complex.

Beyond the slogans of struggle and the five-hour speeches, up in the attic, out of the sight of the children of the revolution, lie some nasty reminders of the regime's dark side, things that Western leftists would quite rightly never tolerate at home - political show trials, oppression, censorship, a monopoly of power. Yet then again, maybe some of them would. Perhaps this is exactly what they have in mind for the rest of us if they ever achieved state power.

In the meantime, Merry Christmas and a peaceful New Year to you all.

· henry.mcdonald@observer.co.uk

Castro's rebellious daughter

leads vitriolic radio attack from Miami

As Cuba's communist regime enters its twilight

years, a family feud is fuelling democratic hopes

Cuba after Castro: Observer

special

Ed Vulliamy in Havana

Sunday March 24, 2002

The Observer

A savage new voice of opposition to Fidel Castro's regime is being beamed into

Havana from a Miami radio station. The owner of that voice is Fidel's daughter.

Over the past month Alina Fernández Revuelta has become the latest talk-show host to hit the cacophonous airwaves in Cuba's fin-de-communist epoch.

'Buenas noches, amigos' - good evening, friends - she kicks off the show, entitled Simplemente Alina - Simply Alina. The programme makes no mention of who she is - 'people just know,' she says.

Of all the dissidents hovering over Castro's final years, Fernández may be among the most damaging. 'I do not refer to Mr Castro as my father,' says Fernández. 'I do not love him, I am his exile.'

Fernández's opposition to her father's regime is the stuff of heated family drama. It is also the story of the child who came to hate her father and everything that he represented, and defected to ally herself with his bitterest enemies, a group that has for years plotted in Miami for his downfall.

Disgusted with Cuban politics as a young woman, Fernández joined the opposition, only to find herself persecuted by her father's government. She defected to the US in 1993, travelling on a false Spanish passport and heavily disguised via Madrid, before introducing herself to the Cuban exile opposition - literally, across a table in its unofficial headquarters, the Versailles restaurant in Miami's Little Havana.